[Blog] The Metapolitics of the New Right: “Japan” as a Crypto-fascist Chiffre

Fabian Schäfer

[Nov 2021]

The New Right has truly fetishized Japan. In the past decades, “Japan” has turned into a crypto-fascist chiffre for core aspects of the ideology of the Far-Right. That is to say, by using “Japan” as a code, the proponents of the New Right can publicly express their views and propagate their worldviews without exposing themselves as fascists. As maybe well known, the New Right uses the term “metapolitics” to describe this discursive strategy. The term was coined already in the 1980s by the founder of the French “Nouvelle Droite,” Alain de Benoist, whom explained metapolitics as a “cultural revolution from the right.” Paradoxically, this discursive strategy originates from the thought of an intellectual whom is also an important thinker for the the post-Marxist New Left, namely Antonio Gramsci. Based on Gramsci’s concept of “cultural hegemony”, the aim of the metapolitical strategy is to disseminate Far-Right ideas in the “pre-political” sphere of culture before establishing these in the political public sphere. To put it differently, by skillfully placing these ideas in the public sphere by broadly using codes and chiffre in various media channels, the anti-feminist or racist ideologies will gradually “normalized” over a longer period of time. Thus, instead of using rather well-known and not rarely even justiciable National-socialist or Fascist language or symbols, the New Right is different from the “old” Far-Right because of its shift to these crypto-fascist chiffre and codes to convey and disseminate their ideology.

The encrypted use of “Japan” is a very representative but maybe lesser known example of how metapolitics work as a discursive strategy. Moreover, the example of Japan also can display something more, namely that the rise of New Right, despite its Nationalistic self-centeredness, has a very threatening transnational dimension. Not only do most of the local New Right movements discursively refer to Japan in one way or another in their metapolitical strategy, the New Right has also begun to successfully cross linguistic and cultural borders by mutually referring to each other or to a very formalized and fixed set of metapolitical codes and chiffre in their metapolitical efforts. Japan, as a such a metapolitical chiffre, has not only been fetishized amongst the members of the New Right in Germany and Austria or France, the proponents of the Alt-Right in the USA are also huge fans of the same rhetorical tropes as well. In political terms, “Japan” is understood as a spearhead with regard to implementing the central political and Identitarian goals of the New Right movement in the imagination of the global New Right – with former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō being the “Trump before Trump”, as the former advisor of president of the USA, Steve Bannon, has stated on the occasion of a trip to Japan in 2019 (1). In this essay, I will particularly discuss two aspects of the metapolitical use of Japan as a crypto-fascist chiffre by the German New Right, namely the appropriation of the idea that Japan is being a mono-ethnic nation and the adoration for its restrictive anti-migration policy and as well as for the masculinist and misogynist anti-feminism of Japanese literary figure Mishima Yukio.

AfD’s Japan: Historical revisionism and migration policy

It was in 2019, at the annual Kyffhäuser meeting of the extreme right wing of Germany’s populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Leinefelden that Björn Höcke explicitly praised Japan’s “identity-preserving” restrictive migration policy, stating that it is suitable as a model for Germany (2). In Japan, Höcke argued from a highly questionable revisionist perspective, “Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past) trying to sell (the necessity of; F.S) immigration as a historical and moral duty does not exist.” Only if Germany was to follow the “Japanese way” of migration policy, Höcke continued his speech, more than just the name would remain of Germany and Europe in the future. In his statement, Höcke also explicitly mentioned the spiritus rector of his proposal, namely AfD-functionary Jan Moldenhauer. Moldenhauer is senior advisor to the AfD parliamentary group in Saxony-Anhalt and author of a book entitled Japans Politik der Null-Zuwanderung: Vorbild für Deutschland? (Japan’s Policy of Zero-Immigration: A Role Model for Germany?), published in 2018 by the extreme right-wing think thank Institut für Staatspolitik (IfS; Institute for State Policy) (3). Eventually, Höcke and the party’s far-right wing succeeded with their metapolitical strategy, namely to encrypt the blueprint for their inhumane and racist migration policy by sugarcoating it as the “Japanese Way” of immigration policy: in April 2021, Höcke’s proposal to include a clause mentioning Japan’s migration policy (and not Canada’s) as a paragon was included after little debate into the election platform at the AfD’s national convention (4).

However, it is important to notice that what looks like a very smooth process in hindsight, had in fact been metapolitically prepared for a couple of years already. Within the think tanks of the Far-Right, such as the aforementioned IfS, the idea of Japan being a role model had been ventilated at least since around the 2010s. Martin Lichtmesz, frequent contributor to the institute’s journal Sezession, introduced the myth of Japans still being an “ethnically and culturally homogeneous” nation and thus a counterexample to Europe’s immigration policy as early as in 2016, thus at the time of the peak of the so-called European Migrant Crisis (5). In his opinion, it is thanks to the nationalistic shift in Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party under former Prime Minister Shinzō Abe that Japan had been successfully safeguarded from these dangers. According to Lichtmesz’s verbatim of a public statement by politician Shigeharu Aoyama (LDP) in his concluding remarks, Japan on the contrary had recognized that it could learn from Germany only in one respect, namely with regard to its complete “failure during the migrant crisis”. He concludes his essay by warning that only by following the Japanese way, “internal peace” could be maintained in face of the upcoming “uprooting and massification” of the Germany population against the imminent peril of the “predominance of Islamic monoculture.”

Japan is considered a role model by the German New Right also with regard to successfully introducing historical revisionist arguments into public political discourse as a counter-narrative against the re-educative “national masochism” imposed under Allied occupation after World War II. In Japan as well as in Germany, the main focus of the revisionist discourse lies on re-interpreting the historical account of the past, particularly with regard to the war crimes committed by both countries in World War II. To the proponents of the New Right in Germany, Japan had been far more successful in “normalizing” its account wartime history. In this vein, Japanese revisionists have widely publicized, denying the so-called Tōkyō trial view of history (Tōkyō saiban shikan) imposed by the Allied occupiers and describing the systematic sexualized violence against women during the war as “fabricated problem of the comfort women” (i’anfu mondai netsuzō). In Germany, top politicians of the AfD have begun to try to shift historical discourse as well, for instance by referring to the period of National Socialism as “flyspeck” if compared to the Germany’s glorious cultural history as a whole (Alexander Gauland), or the Holocaust memorial in Berlin as self-destructive “memorial of shame” (Björn Höcke) in public speeches. One of the most important goals of the revisionists in both countries lies in a reform of school education, particularly with regard to an “anti-patriotic” teaching of history curriculum, which is allegedly based on the aforementioned “masochistic” view of history, aiming at introducing a curriculum that favors the formation of “healthy” patriotic consciousness amongst the youth.

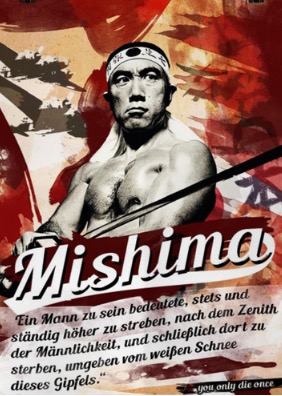

Mishima Yukio: Idolized Masculinism and Death Wish

Intellectuals of the Far-Right, such as Japanologist Winfried Knörzer, argue that Japan, different from Germany, had succeeded in maintaining a self-confident nationalism. In a contribution to the aforementioned journal Sezession, he argues that it is particularly the historical continuity of the imperial house in Japan that had preserved a symbolic integrity amongst the Japanese people and had maintained a “real continuity” between the present and the past (6). By contrast, in Germany “the myth of a zero hour has demonized the country’s history prior to 1945 into a chimera of evil.” By placing the Japanese emperor, i.e. the Tennō, at the center of his revisionist argument, Knörzer relates to a core element of Far-Right discourses in Japan. One important proponent of this view of history is writer and actor Mishima Yukio, a literary and intellectual figure that is rather well-known even beyond Japan’s borders.

Together with other intellectual figures idolized by the New Right such as Julias Evola to Ernst Jünger, Mishima is frequently employed as a code for a hyper-masculinized and self-sacrificing revolutionary stance against the postwar political order imposed by the USA by the proponents of the New Right in Europe as well as the Alt-Right in the USA. One of the biggest fans of Mishima in the Germanophone New Right might be the front man of the Austrian section of the Identitarian Movement, Martin Sellner, whom also happened to be married to female Alt-Right influencer Brittany Pettibone. Before being permanently banned from Twitter in late 2020, Sellner publicly expressed his admiration for Mishima on numerous occasions. In 2016, for instance, he posted tweets such as “i adore Japan because of mishima” (sic.) and “Mishima and a death wish in the morning :D” to publicly express his esteem for Mishima. Marking the fiftieth anniversary of Mishima’s demise, Sellner and his close friend Martin Lichtmesz, being a self-confessed fan of Mishima himself, produced an hour-long YouTube-video on the occasion of Mishima in November 2020. In his own publications, Lichtmesz idolizes Mishima as a poet and dreamer “surrounded by the tantalizing breath of Hades.” With Sellner being banned from YouTube in 2020, the video is not accessible any longer.

Source: https://www.bonvalot.net/die-identitaeren-und-der-japanische-faschismus-ein-code-fuer-putsch-gewalt-und-diktatur-743/

Conclusion

As we have seen, “Japan” has become an integral part of the metapolitical strategy to use crypto-fascist codes and chiffre to convey sometime very far-right extremist messages. Metapolitics operate in a field of legal vagueness and discursive nuances, in which it is always an option for the Far Right to claim that one’s statement had either been misunderstood or taken out of context. Journalist Thomas Assheuer once described this strategy of the New Right as “tactical self-denial”. Furthermore, as the case presented here was able to proof, the employability of “Japan” or “Mishima” as an easily decodable crypto-fascist code for insiders has been the result of a long-term metapolitical strategy. Actors ranging from publicists of Far-Right think tanks such as the IfS, to politicians of the rightwing populist political Party AfD and creatives in the field of popular culture have been working on establishing “Japan” as an non-justiciable but highly effective chiffre for radical Far-Right positions.

It based on this kind of shared vocabulary and imaginary that the global Far-Right can globally connect on the discursive level as well. With the help of digital media that proponents of the Far-Right can not only mutually and strategically refer to Far-Right policies in other countries, such as the “Japanese way” of a restrictive immigration policy or revisionist discourses, but have also managed to create a global vernacular and imagery of crypto-fascist symbols and chiffre, ranging from intellectual discourse of protofascist and fascist thinkers such as Ezra Pound, Carl Schmitt, Dominique Venner, and Mishima Yukio as well as a wide range subcultural references to movies such as Fight Club to aforementioned Mishima comic. Especially the latter can function as a low-threshold gateway to even more extremist content produced by the Far Right and thus as an effective metapolitical instrument for a transnational mobilization efforts.

Footnotes:

(1) https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/29/opinion/abe-trump-japan-illiberal-authoritarian-turn.html

(2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYzMPVtKPo0

(3) Moldenhauer, Jan (2018): Japans Politik der Null-Zuwanderung: Vorbild für Deutschland? Steigra: Institut für Staatspolitik.

(5) Lichtmestz, Martin (2016): „Armin Nassehi und die ‚ethnische Homogenität‘“. Sezession. https://sezession.de/53540/armin-nassehi-und-die-ethnische-homogenitaet [letzter Zugriff 02.07.2020].

(6) Knörzer, Winfried (2005): „Der Tenno und der General.“ In: Sezession 9/April, 50–52.

(7) Hans-Joachim Bieber (2014). SS und Samurai. Deutsch-japanische. Kulturbeziehungen. 1933-1945. München: Iudicium.

(8) https://hydra-comics.de/produkt/comicroman-yukio-mishima-der-letzte-samurai/

(9) Schick, Jonas (2020): „Netzfundstücke (58) – In memoriam, Comic, Hydra.“ Sezession (Online). https://sezession.de/63244/netzfundstuecke-58-in-memoriam-comic-hydra. [letzter Zugriff 02.07.2020].

(10) This quote is from Mishima’s novel Honba (Runaway Horses; 1969), the second novel in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy.