[Article] “From Y”: A mixed-method analysis of the Twitter Account of Abe Shinzō’s killer

Abstract

Reports on the murder of former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, even after details on the perpetrator’s Twitter account were made public, reinforce ideas that 1) the perpetrator’s motives were not inherently political and 2) stem from a personal grudge against the Unification Church and the belief that Abe Shinzō was deeply tied to this group. Through a mixed-method content and discourse analysis of his Twitter account, we find that 1) the perpetrator’s worldview is distinctly political and ties into the belief systems associated with online right-wing and misogynist sub-cultural communities, and 2) his account reads as a fragmented manifesto combining self-victimized accounts of his past intertwined with the above political views. Based on these findings, we argue that the perpetrator’s actions are driven both by his political beliefs and by a sense of manifest destiny and urgency we associate with internet-radicalized terrorists and the highly networked communities driving them.

(This research article is part of a larger project that deals with the immediate aftermath of the murder and its repercussions on social media.)

Introduction

On July 17th, 2022, information concerning the Twitter account of the suspect in the Abe Shinzō murder rapidly spread across social media and through a variety of Japanese tabloids.[1] Although the account in question was suspended for violating Twitter’s “perpetrators of violent attacks policy” within a day after this information was brought to light,[2] copies of the account’s tweet history were promptly distributed on other websites and the content of those tweets continue to be referenced in various news articles. Not unexpectedly, among such news articles, a clear focus lies on tweets that tie into the perpetrator’s well-established motive for the murder: his resentment for the Unification Church (a syncretic new religious movement centering around its founder Sun Myung Moon) and its alleged connections to Abe Shinzō. On July 18th, for example, NHK World broadcast a news segment on the alleged Twitter account, stating that “Such posts include one saying that the only thing he hates is the Unification Church, so he doesn’t care what happens to the Abe administration.”[3] As another example, the Asahi Shimbun not only reiterates the same tweets, but further highlights various tweets expressing childhood experiences and how they connect to his family’s suffering at the hands of the Unification Church (Asahi Shimbun AJW 2022b).[4]

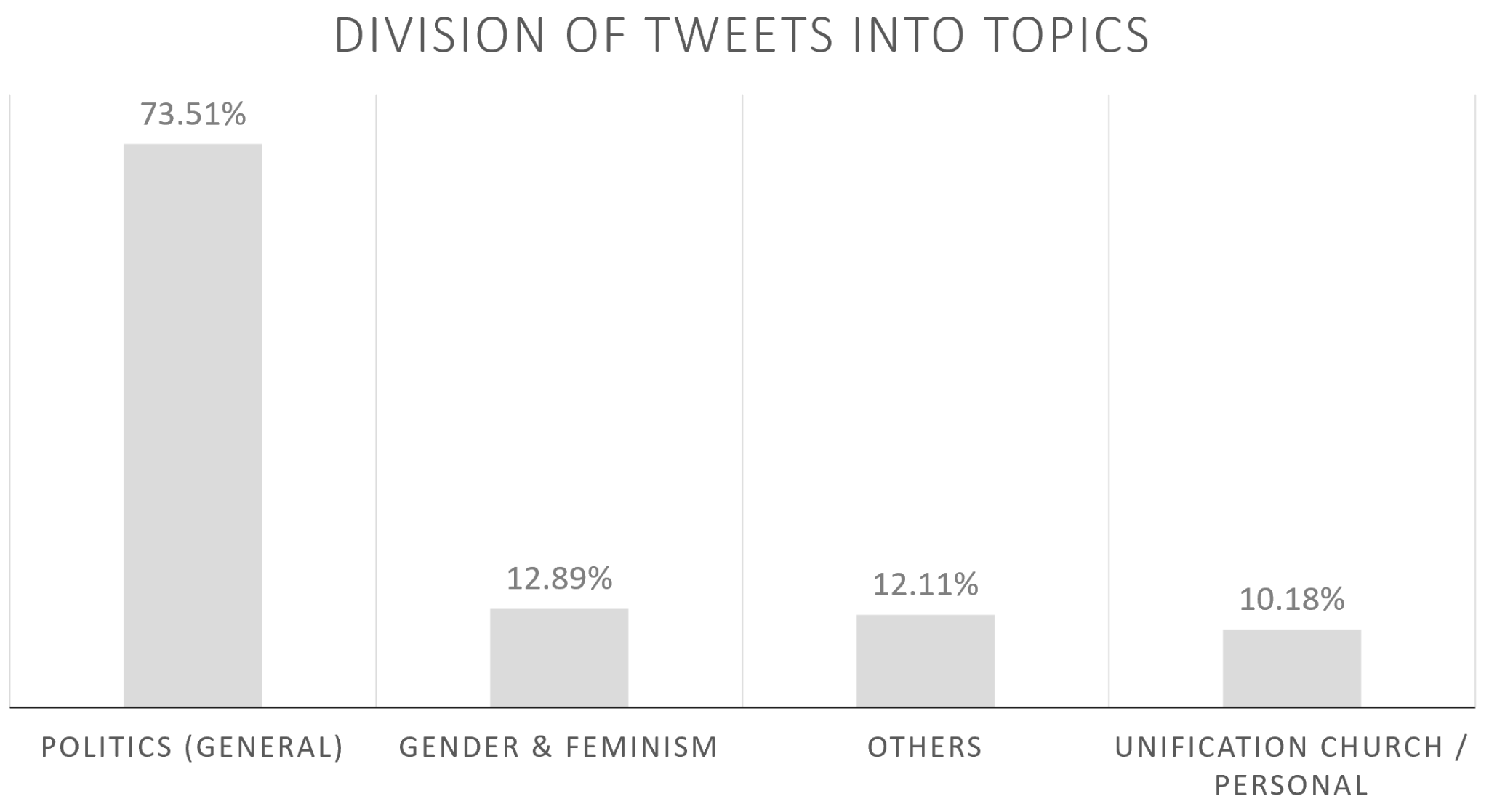

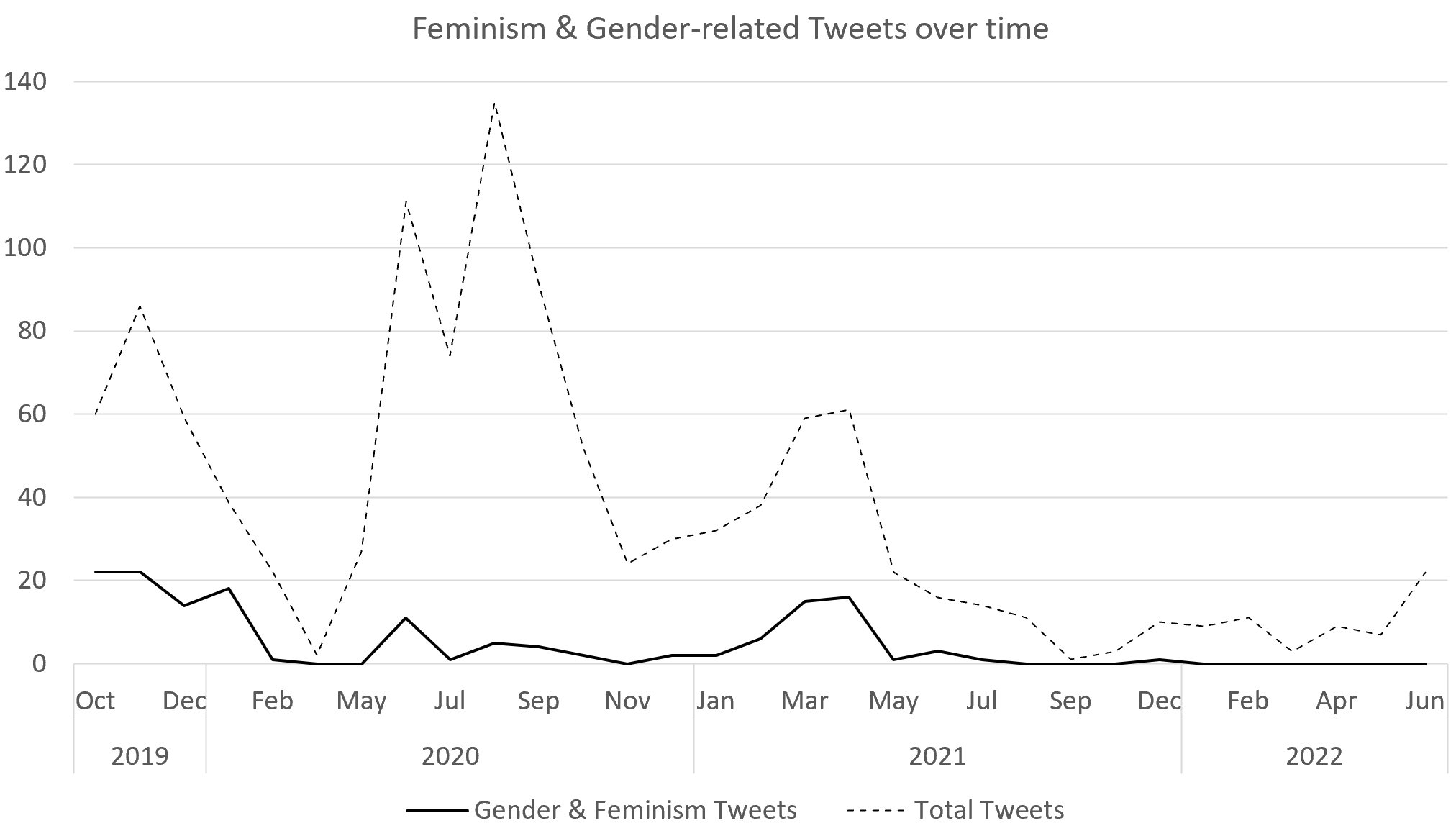

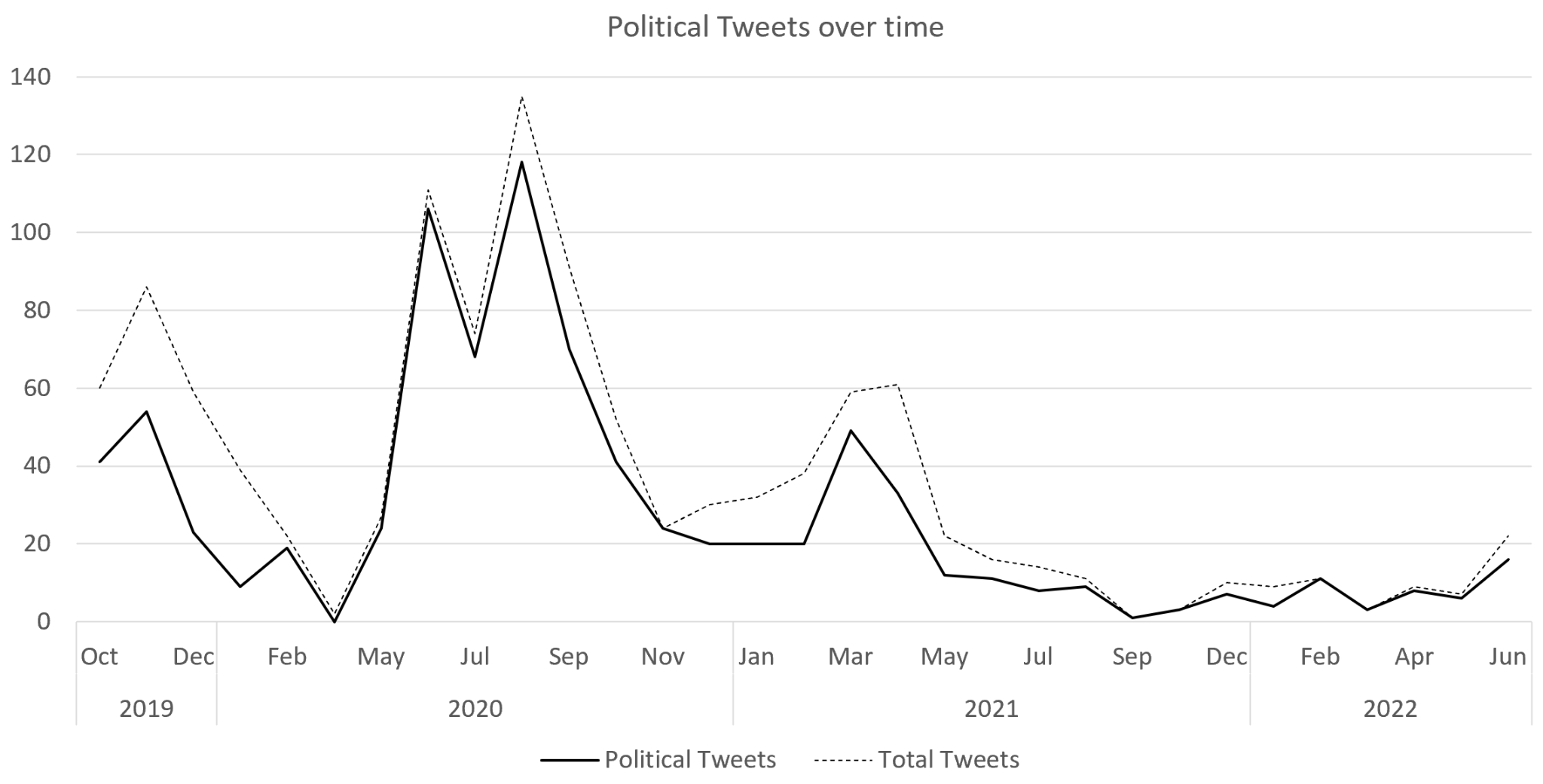

A common thread among such articles, however, is to use a select amount of the perpetrator’s tweets to frame the murder as one committed out of a purely personal grudge, devoid of any political intentions. In order to understand to what degree such different framings of the perpetrator are accurate or require further nuance,[5] we conducted a mixed-method analysis of his alleged Twitter account by applying 1) methods of computational linguistics to structurally classify the Twitter corpus, and 2) a critical discourse analysis of a categorized sample of tweets.[6] Through the aforementioned methodology, we identified three major discursive practices (as could be seen in Figure 1) which we will view in detail below: 1) a mixture of right-libertarian and conservative commentary on political topics (both on a national and a global scale), 2) anti-feminist and misogynist beliefs, and 3) the narrativization of the Unification Church’s impact on his personal life.[7] Finally, we open a discussion into the wider importance of these findings in our understanding of the perpetrator’s motivations.

Analysis

For our quantitative analysis, we used a Python-based custom-built framework to 1) obtain the corpus before it was taken down, 2) obtain various account-metrics that give insight into the usage of the platform and 3) to systematically categorize the corpus of tweets.[8] For our initial computation-linguistic analysis, we used the Japanese text segmentation tool MeCab (using the IPAdic-Neologd dictionary) and the quantitative content analysis software KH Coder. Basing ourselves on the results of a frequency analysis and a co-occurrence network of proper nouns,[9] we constructed a typology of four categories (“politics”, “gender & feminism”, “Unification Church & personal information”, “other”) which we reiteratively refined during our deep reading of the perpetrator’s own tweets (e.g. excluding likes and retweets).

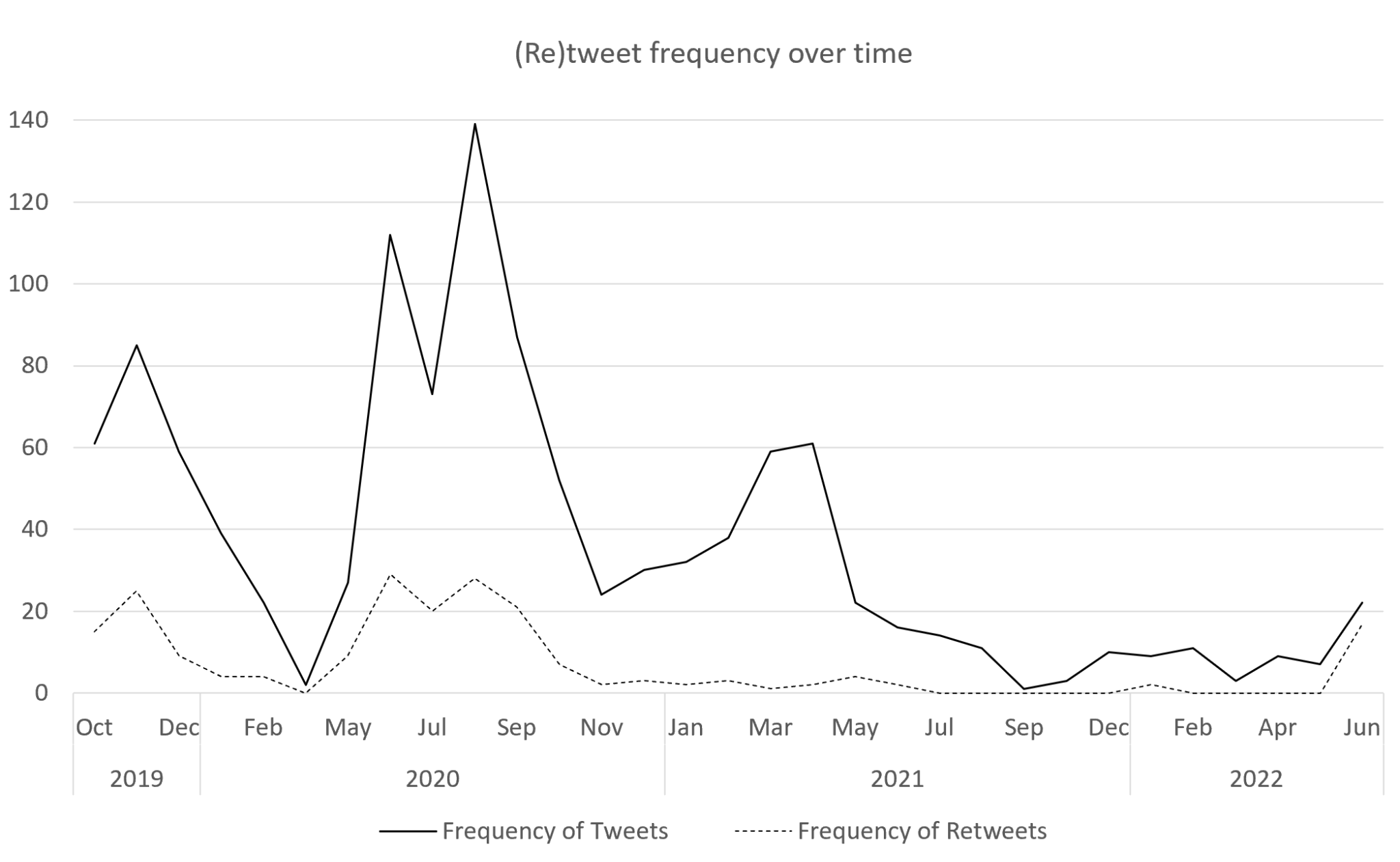

Our corpus collected from the Twitter account in question, “@333_hill”,[10] consists of 1349 tweets (tweeted between October 13th, 2019 and June 29th, 2022), of which 209 are retweets, 456 are commentary on other accounts’ tweets (quoting them in the process), and 128 tweets tag other twitter accounts as a form of direct response.[11] The referenced accounts are a mixture of private users with whom the perpetrator often engages in ongoing conversations or discussions, as well as public accounts of public figures (such as right-leaning LDP politician Amari Akira and journalist Arimoto Kaori) and media-outlets (such as Litera, Gendai Biz, and the far-right social media aggregation website Anonymous Post).

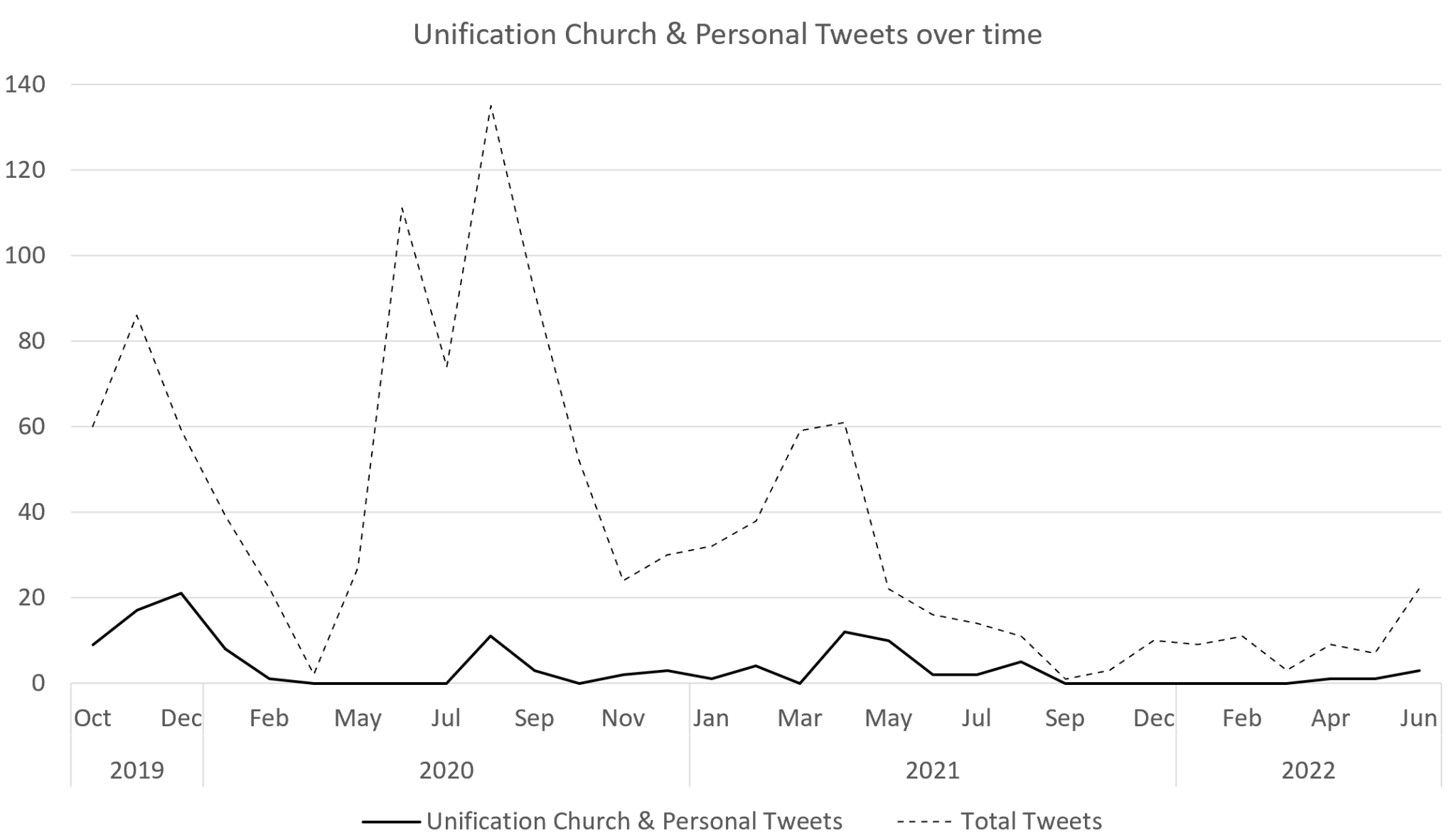

The perpetrator registered the account on October 13th, 2019 and used it immediately after: the first tweet, a quote-type tweet, was made only 23 minutes after registration, followed immediately by replies, retweets, and tweets tagging other accounts.[12] Nevertheless, according to the Asahi Shimbun, when the account was publicly linked to the perpetrator on the morning of July 17th, it had zero followers and followed only two other accounts: Bunshun Online and a freelance writer critical of the UC (Asahi Shimbun AJW 2022c). Given the metrics described above (i.e. ongoing interactions with other accounts), it could be assumed that the account had followed a variety of other accounts over the span of the past three years. As can be seen in Figure 2, the account owner used the platform extensively (with heavy peaks particularly during the initial COVID-19 lock-downs in Japan), and, as seen through the highly interactive nature of his tweets, beyond the scope of what could be called a semi-public, self-referential diary. We must therefore account for the possibility that the account owner deliberately removed his followers and accounts he himself followed, yet refrained from further limiting access to his account (by deleting it altogether or locking it to followers-only), at some point before his assault on Abe Shinzō.[13]

Unification Church & Personal Details

Several hours after the account was initially created, the account retweeted an older Tweet (September 17th, 2019) by the Twitter account of tabloid newspaper Nikkan Gendai, which links to, and summarizes an article entitled “Abe’s new cabinet is like a ‘cult cabinet’…12 members are affiliated with the Unification Church and 12 with Nippon Kaigi” (Nikkan Gendai Digital 2019). Although the article explicitly mentions Abe as one of those affiliated members, the perpetrator posted several tweets in response defending the Abe administration.[14] According to the perpetrator, due to the Unification Church’s ultra-nationalist politics, the organization should be seen as “the enemy of the entire world and, naturally, the irreconcilable enemy of Japan.” While acknowledging that Abe Shinzō, too, could be considered “a far-right nationalist”, to him the two are incomparable: “compared to the horror of the Unification Church, a little political deviation is merely a cute thing. […] To equate [the Abe administration] with the Unification Church would be disrespectful.” Nevertheless, several hours later on the same day and almost as to clarify that any future action would not be motivated by a personal grudge against the Abe administration’s political stance, the account posted a since-widely reported Tweet with the following message: “I only hate the Unification Church. I don’t care what happens to the Abe administration as a result.”

Although it was initially suspected that the perpetrator might have been susceptible to disinformation or conspiracy theories,[15] indications thereof in his twitter account are virtually nonexistent.[16] Instead, although on various occasions retweeting articles on alleged ties between political entities and the Unification Church, the perpetrator summarizes his interpretation of Abe’s direct ties thereto as follows: “The Anpo Struggle and later the [Japanese university protests], things that would be unthinkable today, were being done then by both the right and the left. Among them, Kishi invited the Unification Church simply because it was of use to the right. I would not be surprised if Abe, who followed Kishi and created the framework for the new Cold War […], inherited the DNA of lawlessness.” In other words, the perpetrator refrains from framing either Kishi or Abe as having deeper religious ties to the group and in effect views their affiliation as a form of Cold War era political instrumentalization.[17]

The perpetrator’s grudge against the Unification Church has been utilized in claims that the murder of Abe was, in fact, not politically motivated; a claim which ignores, as shown, the majority of his Twitter account contents, runs risk of an unnuanced view of politics, and presents a perspective that effectively avoids uncomfortable topics. This claim is illustrated on one hand by a variety of analogies (one tweet refers to them as “scum as bad as or worse than Nazis”), and on the other hand, through the intertwining of his opinions on the Unification Church with detailed descriptions of the trauma he endured during childhood, including what he perceives as a “decisive betrayal 25 years ago that distorted my life to this day,” by his mother’s neglect.

Indeed, tweets on the Unification Church often intersect with long series of tweets that are not aimed at anyone in particular and, reminiscent of online manifestos, contain detailed recollections of the perpetrator’s past and his relationship with family members, including his younger brother, father, grandfather, mother and ex-partner.[18] The perpetrator portrays himself as a victim of on one hand an unloving mother that fell for the Unification Church, and on the other hand, a patronizing grandfather whose expectations he could never fulfill. With tweets such as “I know the cause of my emptiness. Evil takes advantage of good,” “I’m not friendly and I don’t know how to respond to love,” and (in reference to Osamu Dazai’s novel No Longer Human), “I am unfit as a human being in the sense that I just kept on pretending,” the perpetrator then follows up on these tweets by suggesting the impact it had on his personality,[19] or by alluding to an inevitable use of violence. Referring to alias of the then-underage perpetrator of the 1997 Kobe child murders, for example, one such tweet states “I should have caused something like Sakakibara did, who was the talk of the town at the time.I always thought that was the only way I could have been saved.”

Nevertheless, the perpetrator’s frequent positioning of the Unification Church and its supposed Korean ethnonationalism as inherently anti-Japanese (and possibly related to North Korea) expresses a political framing of the Unification Church beyond the forms of personal trauma: “The Unification Church, the far-right Korean nationalist party that boldly claimed that Korean would replace English as the lingua franca […] is the enemy of the whole world and, naturally, of Japan”. Furthermore, rather than condemning ethno-nationalism or religious elements altogether, he argues for strengthening the Japanese identity, even going so far as to frame Shintoism as “needed to counteract the poison of the Korean [Unification Church].”

Finally, on several occasions he belittles the experiences of so-called Shukyō Nisei (宗教二世) – children of parents that have joined a religious group – who express personal grievances on Twitter, stating that such personal pains are incomparable to the large-scale damaging actions of the Unification Church. In one thread of comments, placed in reaction to his retweet of such a Shukyō Nisei account, he starts by criticizing the Tweet author but finishes by writing: “I contact you because I thought that you must hate the Unification Church too. If you hate the Unification Church, you must hate it very deeply and profoundly. If you have unforgivable feelings for the Unification Church and the Moon family, please contact me. From Y.”[20] This illustrates how, rather than an act of vengeance orchestrated from a personal grudge against the man or family he believed to be responsible to strengthening the Unification Church in Japan, his actions appear to stem from an internalized feeling of necessity to stop what he frames as an ‘anti-Japanese, Korean cult’ from further impacting Japanese society.

Feminism & Gender

The account owner has, over the duration of his entire Twitter activity, repeatedly tweeted on issues relating to women and women’s rights (accounting for about 10% of the corpus, excluding retweets), including discussions on the wedding of former imperial princess Mako, on Shiori Ito, and the #MeToo movement in Japan. Often shifting the topic to DNA and genes, the author establishes, throughout replies, discussions and general tweeting, an extremely essentialized notion of gender and sexual attraction in terms of what he imagines to be an inherent, biologically-determined desire to reproduce the strongest offspring. Further, he argues that from this biological need stems then the female nature to seek the most dominant men on the societal ladder, which he frames as evident from his allegedly observed lack of “women marrying those with physical or mental disabilities.”[21] In his narrative, once proper suitors are found, women would engage in a mutually beneficial trade of sexual intercourse, as a form of labor, for the benefit of both physical, short-term safety and long-term safety on a societal level.

Due to these perceived inherent characteristics of women, the author expresses concerns as to what would happen to society once women’s rights and sexual freedom were guaranteed, something that he states “is unprecedented in the history of mankind.” This ties in with explicit criticism on the topic of feminism. Throughout his tweets, the author describes his understanding of feminism as an inherently left-wing, reductionist, and fundamentalist belief system that pits men versus women, latently antagonizes all men, and would threaten society itself if enforced on a large scale. As one Tweet puts it: “if feminism (which affirms only women’s instincts) rules the world, civilization will be easily destroyed.” This misunderstanding of feminism further ties in with the ultra-conservative beliefs the author holds in regards to sexuality and procreation. To the author, feminism fundamentally abhors men’s sexual desire (implicitly denying men of their sexual nature) and thus is framed as a selfish movement “for the benefit of only one gender.”

Moreover, between mid-October 2019 and late January 2020, and once again early August 2020 (a total of approx. 1% of total tweets) the account makes explicit references to incels.[22] While never applying the term to himself (instead on several occasions mentioning an ex-girlfriend), he continuously employs a sympathetic tone throughout all his tweets. In December 2019, for example, the account tweeted: “free love and feminism have been around for at most the last 100 years, so if incels would have been born before that time, they might have been fine human beings.” In a Tweet posted a month earlier, the author writes that “it is the Chads that feminists should be attacking instead of incels. Incels are powerless against women until they explode out of hatred.” There, he refers to the archetypal, imagined ‘Other’ of incels: ‘Chads’. As a trope of a confident, dominant and charismatic man, a ‘Chad’ is often depicted as a ‘bad boy’ figure that women (from the viewpoint of the highly-contested theory of evolutionary psychology popular within such circles) are supposedly biologically attracted to despite the threat of neglect, violence and abuse that these men would impose. In light of the author’s biologically-reductionist arguments brought up above, the use of this jargon, specific mainly to English-language incel and wider misogynist subcommunities, shows that the author had to some extent in-depth knowledge of such communities, and again, in a transnational manner, reveals the author’s engagement with various global, highly online, subcommunities.

The perpetrator’s initial tweets on this subcommunity tied-in to his deeply personal interest in the 2019 film Joker, and its titular character Arthur Fleck. The character of the Joker has long been associated with both mass shooters and those within the incel community, and, before its release, a significant amount of media attention was drawn to the possibility of real-world violence inspired by the film. Between mid-October 2019 and late January 2020 and again on mid-August 2020 (for a total of 14 tweets containing the terms Joker and Jōkā ジョーカー), the author wrote various tweets signifying his close connection to the character and his annoyance at the incel-association, such as, on mid-October 2019, “I will not allow anyone to tarnish the sincere despair of the Joker.”[23] The author’s close, sympathetic attachment to the character and the author’s own plight is further revealed on two separate occasions. First, in January 2020, he tweets: “My grandfather would be posthumously humiliated, but we won’t know that until 10 years later. Why did the Joker turn into the Joker? What made him despair? What does he laugh at?” Again, mid-August 2020, he tweets: “because of the Corona pandemic, it feels as if the Joker is in a world apart. Hak Ja Han probably won’t be coming this year. Is that a good thing or a bad thing for me?” referring to Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon’s wife, whom the killer has since confessed to have planned to assassinate when she was supposed to come to Japan.

Politics

The perpetrator’s most prominent use of his Twitter account is to discuss and comment on contemporary political news topics. This commonly takes place in the form of replies to opposing views (either replying directly to the user in question, or by quoting them), after which he will then rephrase and elaborate his opinions as untargeted tweets on his public feed. The very first tweet of this account, for example, was a dismissive reply to an account critical of the coronation ceremony of the Japanese emperor during the COVID-19 crisis: a topic elaborated upon over the following hour in various tweets on the emperor system and its post-war symbolic importance to Japan. Immediately after, the perpetrator expressed his doubts over the validity of a 2014 The Times article shared by a public Japanese media figure, which claims that the NHK was forced to remove direct mentions of the comfort women system (Parry 2014). He followed this up with tweets containing negative sentiments towards both South and North Korea and towards China, setting the general tone for the remainder of his explicitly political tweets – views that are further propagated by his retweets of tabloid articles aligning with such views.

Furthermore, although often engaging with news topics as they are unfolding and actively being discussed on online media, a majority of the political commentary provided by this Twitter account can be summarized as driven by a Cold War narrative that positions Japan within rising tensions between China and the United States. Such tweets often involve topics on measures of national safety and the right to collective self-defense and constitutional reform, and are posted in reaction to what he perceives to be a growing threat from China to Japanese sovereignty. This logic is aptly summarized in a June 2020 Tweet arguing the importance of the LDP as ruling party: “the new Cold War, old-fashioned as it may be, forces a choice: the West or the East, the US or China, capitalism or socialism, and there is no force other than the ruling party that can satisfactorily side with the West.”

While at various points admitting party-wide corruption within the LDP, it is precisely that above mentioned aspect that retains his support for the party and reduces his views of the opposition to a ‘leftist’ or even ‘communist’ entity. In his own words, “the LDP’s one-party dominance will, and should, continue for as long as the U.S.-China confrontation goes on and opposition parties retain only an old leftist view of the security situation. […] I would prefer that there be no corruption, but that does not mean that I would choose a communist government. The amount of corruption is one of the myriad of selection criteria […] As long as the domestic liberals are led by communists, there is no tomorrow for Japan.” Moreover, although inclined to support Ishiba Shigeru over the LDP’s Abe faction,[24] as well as expressing a dislike towards Suga Yoshihide as Abe’s successor,[25] he consistently demonstrates a certain level of approval for Abe’s personal achievements and for the Abe administration’s struggle to revise the constitution, as illustrated by a series of tweets from August 2020:

“If we strictly apply the criterion that the violation of the Constitution means great evil, we could not even have had the Self Defense Force (SDF) in the first place. If the SDF did not exist and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty was not established, there would be no postwar Japan. […] It is dangerous to make ‘Violation of the Constitution’ an absolute creed in a country that cannot revise its Constitution and cannot affirm the right of collective self-defense head-on, even in the midst of the US-China confrontation. Kishi’s Security Treaty struggle that established the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty system, and Abe’s Constitutional struggle for Japan-U.S. collective self-defense… The outcome of such meaningful history will prove Kishi and Abe were right. Postwar Japan chose to prosper rather than protect the Constitution and destroy the country. The irony is that the Constitutionalists are able to exist because postwar Japan did not become a communist nation due to the disregard for the Constitution.”

This logic is further extended to a global scale, as seen in tweets discussing foreign political affairs. Framing the Biden administration as aligning with Chinese interests, for example, the perpetrator speculates about the possibility of U.S. forces withdrawing from Japan and thus in effect “surrendering the Senkaku Islands and Okinawa to China” and in consequence enabling the “establishment of Chinese hegemony in East Asia.” These views, as well as the necessity for the LDP to remain in power, are articulated most prominently through a series of tweets in late June 2020, claiming that:

“If Biden wins the U.S. presidential election by mistake, Japan may be cornered into either capitulating or fighting China. China is not the kind of country that will be happy to just give up the Senkaku Islands. At the very least, it has the will and the ability to become the dominant power in Asia, both militarily and economically. One only has to look at Hong Kong to see what is wrong with that. If one is opposed to the LDP draft constitution, one must be in favor of the right of collective self-defense to keep the U.S. at bay if there is a possibility that the U.S. will make concessions to China. That is what the opposition does not understand at all.”

Whereas a certain level of respect is displayed in his attitude towards China due to its economic and military growth, no such traces exist in his tweets on topics related to South Korea, and he often resorts to derogatory language instead. In the argumentation of the perpetrator, the goals of the Unification Church and the goals of ethnic Koreans intrinsically align; both allegedly driven by an anti-Japanese form of ultra-nationalism. From this perspective a dislike for anything related to South Korea, North Korea, and ethnic Korean diasporas in Japan is not unexpected, as seen in tweets such as “Korea is a country that can only have a negative impact on the people around it, no matter what they do with their ethnicity,” and “I will never forgive the Koreans as a group and I will never forgive the Japanese who side with them.” Nevertheless, beyond personal grudges, this sentiment too can be read within the aforementioned neo-Cold War framework. One such example pertains to former South Korean president Moon Jae-in’s initial decision, amid ongoing wartime history debates as well as trade and territorial conflicts, to withdraw from the General Security of Military Intelligence Agreement (GSOMIA) – a trilateral military intelligence-sharing agreement between the US, Japan, and South Korea originally set up in order to form a front against North Korea’s nuclear ambitions and China’s influence in the region: “If the new Cold War between the U.S. and China continues at this rate, South Korea must really be an idiot to try to break GSOMIA […]. It is truly a small China.” (late November, 2019).

Furthermore, his perceived understanding of a growing South Korean negative sentiment towards Japan as an expression of ultra-nationalist, anti-Japanese attitude, goes hand in hand with the discussion of major points of ongoing contestation between Japan, the Korean peninsula, and ethnic Koreans in Japan. Although initially not downright denying the comfort women system in its entirety,[26] the perpetrator views it as a non-issue that was resolved after “the Japanese military and the Empire of Japan that operated the comfort women system were forcibly dismantled,” and one that has since been politicized for the purpose of “hating Japanese people.” In one Tweet posted late 2019, the perpetrator describes film director Miki Dezaki’s film on the contemporary contentiousness of the comfort women system as “proof of the malice” of “self-proclaimed liberals.”[27] In several other posts, he specifically targeted ethnic Korean schools in Japan (Chōsen gakkō), as well as Twitter accounts calling out discriminatory practices against those schools and its students: “You guys should just build a Nazi childhood school, a Greater East Asia Co-prosperity kindergarten or a Marxist revolutionary kindergarten and campaign for free education. It’s stupid.” Failing to consider Japan’s history of colonialism, to the perpetrator, the mere existence of these schools in Japan is a refusal from Korean ethnic minorities to assimilate, as well as an indication of North Korea’s attempts to attack Japan from within: “The Japanese are not the enemy, the whole world is the enemy of North Korea. If you care about your children, you should condemn their parents who send them to Korean schools and allow such schools to exist.”

Moreover, in calling out those who point out discriminatory practices, he appropriates terminology traditionally associated with left-leaning, progressive movements, such as racism and hate speech. In particular, he implies that students refusing to assimilate and continuing to wear national symbols are the real racists: “wearing ethnic costumes on a daily basis in modern Japan is nothing but a sign of being a nationalist and a racist (sabetsu shugisha).” According to his views, Japanese people who use terms such as ‘hate speech’ and ‘discrimination’ in calling out xenophobic and discriminatory behavior towards Korean minorities, are misguided: “In Japan, anyone who uses the word “hate” is subconsciously nationalist. A pro-Korean nationalist, that is. […] Those who call for anti-discrimination are the actually most discriminatory and belligerent, because such calls have become the most powerful weapon of our time.”[28]

Finally, to highlight the perpetrator’s knowledge of practices associated with online subcultural spaces such as the anonymous messaging board 2channel,[29] we examine a brief interaction in which the topics of COVID-19, his negative sentiment towards China, and contested history intersect. Although tweeting dominantly during the COVID-19 lock-down, the perpetrator has refrained from extremist or conspiratorial positions on the virus, instead aligning with more liberal or libertarian views on the topic. He brings up concerns over the economy as well as over rising suicide among women during the lock-downs, but focuses particularly on news reports on the use of masks, suggesting that ‘policing’ masks invites a form of ‘authoritarianism’ or ‘totalitarianism’. Nevertheless, the perpetrator’s instrumentalization of far-right COVID-19 rhetoric for his own political-ideological views is displayed in early February 2020. A Chinese teenage girl posted her indignation with the author of a popular manga for including a character sharing the name of a WWII-era term for human experiments.[30] Intending to draw out the same level of indignation from a Japanese audience, she attached to her Tweet a drawing in the style of the manga, portraying a character titled “Hiroshima Nagasaki” whose hair resembled a nuclear mushroom cloud. In response,[31] the perpetrator posted 15 tweets over the span of two days, including stand-alone tweets, responses (written in English), and quoted tweets as counter-arguments against the target account’s indignation. Of note, however, is his usage of the phrase “I think it’s time for the identification squad to step in” (tokuteihan no deban 特定班の出番); particularly using a term associated with groups of people online who identify and reveal private information (a practice commonly known as ‘doxxing’ in English), often for the purpose of online harassment. Indeed, the account was the target of online harassment and, right after posting this, the perpetrator posted several English-language tweets tagging the original account and framing COVID-19 as a form of Chinese biological warfare. In other words, to the perpetrator, the severity of the virus and the conspiratorial ideas of the virus as a Chinese biological weapon become cynical assets for online harassment; a common strategy and form of ‘gamified fun’ among online subcultures associated with far-right ideologies (Nagle 2017; Udupa 2019).

Discussion

As we have demonstrated, the corpus of tweets contains a combination of 1) ideological musings and discussions that can be separated into several distinct categories, and 2) a carefully constructed form of storytelling regarding the impact he claims the Unification Church has had on his family and himself, presented in a way that could be seen as a form of fragmented manifesto, describing the perpetrator’s rationale behind his actions and his ideological views.

On a political level, the perpetrator primarily expresses an ideological inclination against anything and anyone that relates to the Korean peninsula or Korean ethnic identity; an expression of xenophobia that is further fueled by the Cold War framework guiding his broader perspectives on Japanese sovereignty, as well as his views on public safety, support for the LDP, and an antagonization of perceived left-wing elements. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the perpetrator utilizes Twitter primarily to discuss and attack opposing views (e.g. in response to other users), after which he would then rewrite his thoughts as a standalone series of tweets on his own profile. This usage of online media, as well as his strongly-voiced political opinions, are not unlike what various scholars have categorized as ‘Netto Uyoku’ (lit. Net-Right): a loosely connected, decentralized group of Internet users, active primarily on social media platforms such as Twitter, the anonymous messaging board 2channel, and communities built around video-streaming (YouTube and Nico Nico Dōga) and disseminating a distinct form of far-right rhetoric. That rhetoric is often aggressively centered on South Korea, North Korea, and China, towards minority groups in Japan, and towards perceived left-leaning institutions such as liberal universities and larger media-outlets, while retaining a cynical, sneering sense of playfulness (Kitada 2005; Tsuji 2008; Higuchi et al. 2019).[32]

By viewing this categorization of ‘Netto Uyoku’ as a Japanese expression of a growing and highly malleable global phenomenon of internet-fueled far-right and libertarian-right ideologies (which include such terms as the ‘alt-right’ or the French fachosphère as other localized instances thereof), we can expand our conceptual understanding of the perpetrator’s actions beyond that of a single man acting out of a personal grudge, and view it as part of a large, transnational series of lone-wolf terror attacks by (young) men both expressing and absorbing their views on subcultural online media. In 2019, attacks in respectively El-Paso, California, Christchurch, New Zealand and Halle, Germany,[33] have been directly tied to participation in far-right or even neo-fascist subcommunities harbored on anonymous chan-like message-boards, and, more broadly, to the bias-reinforcing ‘echo chamber’ effect of the heavily curated online media they consumed. In each of these cases, the killers expressed their worldviews through a manifesto shared with those platforms and highly reliant on in-group references to internet and gaming subcultures, and to Japanese pop-cultural media, signifying a greater decentralized sense of connectivity between them. Although on an ideological level, the perpetrator’s political views – while often leaning heavily to the right – retain elements of liberal and libertarian thought, structurally, it is not unlikely that he operated through the same sense of online hyperconnectivity.

In his anti-feminist postings, the perpetrator expressed a familiarity with both the jargon (e.g. ‘Chads’) and the ideological frameworks of incel communities and what is referred to as the Manosphere.[34] By focusing on DNA, female reproduction, and supposed ‘natural hierarchies’ in sexual attraction, he relies on the pseudo-scientific field of evolutionary psychology and biological deterministic arguments to justify his opposing views on what he views as an extension of left-leaning movements: the #MeToo movement and the Journalist Shiori Ito (who has become the face of this movement in Japan). In these communities, men are framed as victims of a society that increasingly benefits women at their expense, and often intersects with other ultra-conservative communities, framing progressive movements as attackers on traditional values. Although we found this category of analysis distinct enough to separate it from our analysis of his explicitly political tweets, we cannot neglect the intrinsic intersection of both discourse fields: as anthropologist Yamaguchi points out, throughout the 2010s, the development of far-right online communities has increasingly intersected with misogynist, anti-feminist views and enforced traditional gender roles (Higuchi et al 2019).

Again, the violent and deep-rooted misogyny that drives those belief systems have led to multiple instances of terror attacks (as a facet of misogynist terrorism) by perpetrators showing interest in incel subcultures, including in Isla Vista, California (2014), Toronto, Canada (2018) and in Hanau, Germany (2020), and often after sharing an online manifesto. Here, too, should the focus not lie on the underlying ideologies that drove those attacks (as we do not intend to imply that the perpetrator acted out of either misogynist or far-right motives), but rather the hyperconnected, networked communities supporting and empowering the killers to proceed with their actions.

Unable to proceed with his plans to assassinate Hak Ja Han (the wife of the Unification Church’s founder Sun Myung Moon), the perpetrator ultimately targeted Abe Shinzō instead, a neo-conservative, older man whose politics strongly align with the perpetrator. As has become clear from the analysis of his tweets on the Unification Church and his own personal experiences, the perpetrator often frames himself as a victim, not only of the Unification Church, but of society itself. A reading of his tweets, however, suggests that this action was not ‘merely’ a personal, non-political vendetta against Abe, grandson of the prime minister that brought the Unification Church to Japan, and with it, ruined the perpetrator’s family. This conclusion can be drawn from the fact that he 1) sufficiently nuances and relativizes the Abe family’s connections to the Unification Church as being motivated solely by Cold War era political reasons, 2) makes light of others who use Twitter to talk about their shared negative experiences, stating that those experiences pale in comparison to the greater damage the Unification Church causes, and 3) suggests that his past has ultimately destined him to hurt the Unification Church, which he describes as an inherently Korean, foreign and anti-Japanese aggressor. This sense of ‘duty’ is again something that we can trace back in the manifestos left behind by, among others, the Christchurch and Halle shooters, and the call to urgent and violent defensive action that is inherent to these transnational, online milieus.

Although the perpetrator’s ultimate target, Abe Shinzō, on a surface level, appears too distinct from the targets of far-right and misogynist internet-fueled terror attacks, we argue that there are sufficient structural similarities to consider this attack to fit within the same classification. More specifically, we argue that the perpetrator’s deep familiarity with internet-right and misogynist sub-communities (intrinsically linked to a global increase in political violence, terrorist attacks) cannot be neglected in ultimately empowering his actions. In order to prevent similar – or even copycat – attacks from occurring in the future, we suggest correctly categorizing the murder of Abe Shinzō as a terror-attack driven by online-radicalization, and that further attention be given to appropriate counter-radicalization measures in regards to hateful, ultra-nationalist, and misogynist ideologies. Finally, given the distinct shift of focus in the public discourse towards the Unification Church and its ties with the LDP, we further suggest a careful analysis of how the perpetrator continues to be framed and received (including the sharing, in part, of his tweets) in these online subcultures.

Conclusion

Existing reports on the perpetrator based on his affidavit, interviews with acquaintances and family members, and on the above Twitter corpus, reinforce an image of the killer as someone that was mentally unwell, lonely, had a strong personal grudge against Abe, and planned his murder as an unpolitical act grounded in online (dis)information tying Abe and the LDP to the Unification Church. Through a multidisciplinary analysis of a corpus of tweets associated with the perpetrator, we started out with the intention of verifying to what degree the above statements could be corroborated or questioned, and unveiled three distinct layers to the perpetrator’s ideological views and his utilization of Twitter as a social media platform: 1) the discussion of political topics from a right-libertarian perspective (split between attacking counterpoints and sharing mostly right-leaning, bias-confirming online media), 2) misogynist, anti-feminist views, and 3) a splintered, biographical account of his familial experience with the Unification Church.

Given the perpetrator’s understanding of methods (e.g. doxxing), jargon (e.g. ‘Chads’), and argumentation associated with online-right and anti-feminist, Manosphere-related subcommunities tied globally to a rise in so-called lone-wolf terrorism, we argue that we cannot disregard the likelihood the perpetrator, through his interaction with these communities, might have ultimately felt empowered in his actions (just as other alleged lone-wolf killers did in their online connectivity). Furthermore, although his political views might have mostly aligned with Abe Shinzō or, at the very least, the LDP, we have demonstrated that the perpetrator spent a significant amount of time thinking on matters of national safety, which might have ultimately drove the attack: the desire to weaken the Unification Church may not have been one done out of a personal grudge, but from a strong political belief system propagating an inherent need to protect Japan from this Korean, supposedly anti-Japanese element. Existing framings that neglect or downplay this political dimension (as well as to the danger of online radicalization) do nothing but contribute to a collective blind eye to the exact elements that could fuel the next ‘lone wolf’ attack in Japan.

Furthermore, the perpetrator’s distinct usage of his Twitter account includes 1) reposting thoughts he expressed in replies as stand-alone tweets, 2) reportedly attaching the handle to his Twitter account in a personal letter to a freelance journalist right before the attack, and 3) reportedly having 0 followers and only following 2 accounts himself at the time of discovery despite having posted over a thousand tweets in the span of 2 years. Given that, through our analysis, we have demonstrated the corpus to contain a mixture of highly ideological viewpoints as well as a narrative of the perpetrator’s unfortunate past and how it impacts his worldview, we also argue to view this account as, purposefully or not, a fragmented form of the perpetrator’s manifesto.

Bibliography

- Asahi Shimbun AJW. 2022a. “Suspect willing to die to ‘liberate’ members of religious group”. July 18. Available at: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14672929. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Asahi Shimbun AJW. 2022b. “Yamagami yōgi-sha no tsuittā tōketsu `zōo ya kōgeki yūhatsu kinshi’ no kiyaku ni ihan? [Suspect Yamagami’s Twitter suspension as a violation of the ‘prohibition of hatred and provocation of attacks’ rule?]”. July 17. Available at: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASQ7M6DYRQ7MPTIL00W.html. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Asahi Shimbun AJW. 2022c. “`Yūtōsei’datta sanjō yōgi-sha tsuittā ni nokoshita haha e no fukuzatsuna aizō [Suspect Yamagami, who was an ‘honor student’, displayed a complex love-hate relationship with his mother on Twitter]”. July 19. Available at: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASQ7L6HSQQ7LPTIL01R.html. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Dooley, Ben, and Ueno, Hisako. 2022. “In Japan, Abe Suspect’s Grudge Against Unification Church Is a Familiar One”. The New York Times. July 23. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/23/world/asia/japan-unification-church-lawsuits.html. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Higuchi, N., Nagayoshi, K., Matsutani, M., Kurahashi, K., Schäfer, F., Yamaguchi, T. 2019. Netto uyoku to ha nanika. Seikyūsha, Tokyo.

- Hyakuta, Naoki (@hyakutanaoki). “今回の事件を引き起こしたのはメディアだ! 犯人の背景は不明だが、何年にもわたって「安倍が悪い」「安倍こそすべての元凶」などと報道して、多くの国民に安倍さんに対する憎悪を植え付けてきたメディアの責任は大きい。 [It was the media that brought about this incident! Although the background of the perpetrators is unknown, the media is largely responsible for instilling hatred toward Mr. Abe in many people by reporting for years that ‘Abe is bad’ and ‘Abe is the source of everything’]”. Twitter, July 8, 2022. https://twitter.com/hyakutanaoki/status/1545264462399406080. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Kitada, Akihiro. 2005. Warau Nihon no ‘nashonarizumu’. NHK Books.

- Miura, Lully (@lullymiura). “実物の写真は権利関係から掲載できませんが、この保守系著名人らが発起人となった憲法改正を求める会のイベントの大きなスクリーンに映し出されたビデオメッセージの写真を見て、容疑者自身がよく知る旧統一協会のイベントの様子と似ていると考え、繋がりがあるのではと感じたようです。以上。 [Although the actual photo cannot be posted due to copyright reasons, the suspect saw a photo of a video message on a large screen at an event organized by the Association for Constitutional Reform, which was initiated by conservative celebrities, and thought it looked similar to an event of the former Unification Association, which he himself was familiar with, and felt there might be a connection. That is all there is to it]”. Twitter, July 18, 2022. https://twitter.com/lullymiura/status/1548853056896307200. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Nagle, Angela. 2017. Kill All Normies: The Online Culture Wars from Tumblr and 4chan to the Alt-Right and Trump. Winchester, UK; Washington, USA: Zero Books.

- NHK World. 2022. “Abe shooting suspect apparently tweeted resentment against ‘Unification Church'”. July 21. Available at: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20220718_06/. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Nikkan Gendai Digital. 2019. “Abe shin naikaku wa marude “karuto naikaku”… Tōitsukyōkai-garami 12-ri, nihonkaigi-kei mo 12-ri” [Abe’s new cabinet is like a ‘cult cabinet’ … 12 members related to the Unification Church, 12 members to the Nippon Kaigi]. September 17. Available at: https://www.nikkan-gendai.com/articles/view/news/261913. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Nishimura, Hiroyuki (@hiroyuki). “三浦瑠麗さんは、統一教会の代理人をしていた高村正彦さんと共著を出してますか?陰謀論ではなく、事実の確認です。 [Has Lully Miura co-authored a book with Masahiko Takamura, who used to represent the Unification Church? This is not a conspiracy theory, but a fact check.]”. Twitter, July 13, 2022. https://twitter.com/hirox246/status/1547242377739395072. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Parry, Richard L. 2014. “Japan’s ‘BBC’ bans any reference to wartime ‘sex slaves’”. The Times. October 17. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/japans-bbc-bans-any-reference-to-wartime-sex-slaves-s7qtbxr0kc0. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Rich, Motoko. 2019. “A Filmmaker Explored Japan’s Wartime Enslavement of Women. Now He’s Being Sued.” The New York Times. September 18. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/18/world/asia/comfort-women-documentary-japan.html. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Samuels, Richard J. 2001. “Kishi and Corruption: An Anatomy of the 1955 System.” Working Paper No. 83, Japan Policy Research Institute. Available at: https://www.gwern.net/docs/japanese/2001-12-samuels-kishiandcorruptionananatomyofthe1955system.html. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

- Seifert, Wolfgang. 1974. “‘Genri-Bewegung’ und ‘Internationale Föderation für die Ausmerzung des Kommunismus’ (Shôkyô rengô: Die politische Aktivität einer neuen religiösen Sekte in Japan.” In: Die Dritte Welt. Vierteljahreszeitschrift zum wirtschaftlichen, kulturellen, sozialen und politischen Wandel, Heft 3-4: 409-429.

- Tsuji, Daisuke. 2008. “Intanetto Ni Okeru ‘ukeika’Gensho Ni Kansuru Jissho Kenkyu”. http://d-tsuji.com/paper/r04/index.htm.

- Udupa, Sahana. 2019. “Nationalism in the Digital Age: Fun as a Metapractice of Extreme Speech.” International Journal of Communication, 3143‒63.

- Yahoo News Japan. 2022. “Yamagami Tetsuya yōgi-sha no tsuittā ga heisa akashite ita “jōkā” e no kanjō inyū `shinshina zetsubō o yogosu yatsu wa yurusanai’ [Suspect Tetsuya Yamagami’s Twitter shut down, empathy for “Joker” revealed: “I won’t forgive people who defile his sincere despair”]”. July 19. Available at: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/fa46731ec1f21b005516bb6baff7d87636dc4b6b. (Last accessed August 18, 2022).

Footnotes

-

The Twitter account was reportedly sent alongside a longer letter to Japanese freelance journalist Kazuhiro Yonemoto, with whom the perpetrator had earlier correspondence on his blog due to the journalist’s critical stance towards the Unification Church (Asahi Shimbun AJW 2022a). ↑

-

“Any accounts maintained by individual perpetrators of terrorist, violent extremist, or mass violent attacks,” See also: https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/perpetrators-of-violent-attacks. This was further confirmed by the Asahi Shimbun (Asahi Shimbun AJW 2022b). ↑

-

Initially, most major news outlets, including the NHK (NHK World 2022), avoided direct references to the Unification Church and referred to it as “a religious group” or tokutei shūkyō dantai (特定の宗教団体). ↑

-

On July 19, the Asahi Shimbun further reported on the Twitter account, focusing on the personal tweets accounting the perpetrator’s “unfortunate circumstances of his childhood and his mixed feelings of love and hatred toward his mother” (Asahi Shimbun AJW 2022c). One exception to such articles is a July 23 The New York Times article which summurizes his Twitter account stating that “amid anti-Korean screeds, misogynistic musings about incel culture and commentary on Japanese politics, the account — which has been suspended — describes a painful childhood and a seething fury at his mother’s allegiance to the Unification Church. He blamed the relationship for his own failings in life” (Dooley and Ueno 2022). ↑

- Although it is not our intention to further amplify his ideological beliefs (we have, for example, made the conscious decision not to use his name in this paper), the likely framing of the killer as someone who was motivated purely out of personal rather than political reasons (e.g. a grudge for the church that he claims to have ruined his family), risks viewing the incident as isolated from his greater ideological beliefs, as well as from the possibility that the perpetrator engaged and intersected with various online subcommunities that have been associated with a surge in individually-perpetrated terror attacks all over the world. ↑

-

We categorized the corpus according to a typology of keywords matching specific topics, and manually sorted follow-up tweets or ambiguous tweets through a close reading. ↑

-

Although these types of tweets can and do intersect, we find the content and positions taken distinct enough to warrant these particular categories. Tweets that fit neither of those categories are sorted as “Other” and include posts such as opinions on local celebrity scandals, tweets on Japan’s feudal military history, philosophical musings, links to YouTube music videos, etc. ↑

-

For a more thorough look in the data this analysis procured, please refer to the graphs attached to the appendix of this document. ↑

-

The account’s ID name (“333_hill”) and username (“Silent Hill 333”) were most likely made in reference to the horror videogame series Silent Hill, which features a religious doomsday cult as the dominant antagonist element. ↑

-

A total of 115 unique accounts, although these tweets often tag several accounts at once. ↑

-

This suggests that the perpetrator was sufficiently well-versed in the intricacies of the platform, and might even have had prior experience with the platform through a former, or second account. ↑

-

We must nevertheless also account for the possibility that, indeed, the lack of followers and followings was constant, and that his feed was solely based on any topics of interest he might have set manually in his settings, with content algorithmically curated further according to his participation and engagement with certain topics and ideas. However, in such cases, Twitter continuously recommends users to follow certain accounts that fit their interest, which again makes the consistent zero following an at least questionable scenario. ↑

-

Something he does on various later occasions, as well: on August 7th, 2020, he states that “the source of the theory that Senator Kawai is a senior member of the Unification Church, […] is extremely suspicious. The only evidence is probably that Congressman Kawai has attended Unification Church events in the past.” On November 9th, he further tweets the headline of a Harbor Business Online tabloid article titled: “Nine Unification Church-affiliated cabinet members. The Kan administration’s relationship with “new religions, spirituality, and pseudoscience” is no different from that of the Abe administration.” ↑

-

Initially the murder was blamed on a perceived ‘Abe-bashing’ allegedly taking place in mainstream media, a term propagated by historical revisionist neo-conservative media pundits such as Hyakuta Naoki (2022). Since then, pro-Abe voices have gone to certain lengths depicting the Abe family’s ties to the Unification Church as conspiracies all together. ↑

-

One exception is a Tweet which shares a contribution to the Sankei Shimbun-affiliated online tabloid iRONNA, written by the conservative political commentator and media personality Lully Miura. The Tweet wrongfully identifies a photograph of Abe speaking at at a Utsukushī Nihon no kenpō o tsukuru kokumin no kai (美しい日本の憲法をつくる国民の会, “People’s Association for Creating a Beautiful Constitution of Japan”) event as one taken at a Unification Church event. In response to this, Miura wrote that the killer was brainwashed by conspiracy theories on the internet (2022). It should be further noted that Miura has been been the target of various xenophobic and misogynist rumors, including being a Chinese or North Korean spy. 2channel-developer and Twitter influencer Hiroyuki, for example, insinuated as much by highlighting that Miura co-published a book with a former legal lawyer of the Unification Church (Nishimura 2022). ↑

-

An argument widely accepted among political historians; for examples, see Seifert (1974) and Samuels (2001). ↑

-

The longest of which took place early December 2019 and is 15 tweets long. ↑

-

Twice, the perpetrator shares the results of user-made online personality quizzes. First, he tweeted the results of a quiz to determine how many people would be after his life in the future (10 people, to which he added that “although coincidentally, this could be right”), and, second, to determine whether he is a “psychopath or kind person” (resulting in “100% psychopath”). ↑

-

The Tweet explicitly ends with a “From … to …” phrasing, including the initials of his own name and that of the name listed on the account whose Tweet was retweeted. Although the perpetrator often tags users in response, that was not the case in this series of tweets, posting them instead as a form of open letter. ↑

-

It should further be noted that within these discussions on gender and sex, sexuality is never brought up, instead implicitly viewing straight relationships and biologically-determined gender as an unmovable truth. ↑

-

Short for ‘involuntary celibate’, broadly referring to individuals that identify themselves according to their lack of romantic or sexual experience, but often ties in with wider, online sub-cultures rooted in misogyny and anti-feminist thought. ↑

-

Online tabloid Yahoo News held an interview with author Akira Tachibana in regards to the perpetrator’s retweet of her article on the film on NEWS Post Seven. She states that the perpetrator might have felt kinship to the character due to their shared loneliness, and places his actions in the same category as the perpetrator of the 2019 Kyoto Animation arson attack and the alleged perpetrator of the 2021 Osaka psychiatric clinic arson as examples of “terrorism by lower class citizens” (Yahoo News Japan 2022). ↑

-

Expressed on various occasions throughout 2020, including, for example, clearly in a late August 2020 tweet: “I think that the ideal candidate for LDP 2.0 after regaining power is Ishiba.” ↑

-

“Abe had at least a shred of charisma, even if it was cheating. Ishiba has strong logic. What on earth does Suga have? If he even wants to appeal to his farmer background, he should have a way to speak from the same standpoint as the people, like Merkel has/does.” (January 13th, 2021) ↑

-

The perpetrator nevertheless expresses doubts on various occasions, such as in a Tweet late August 2020 claiming that “it’s certainly possible that the comfort women issue is a false ethnic memory rooted in groundless rumors spread in the Korean peninsula.” Moreover, in March 2021, he refers to Ramsayer’s disputed argument “that the comfort station system was basically a transplant of domestic brothels to the military regime,” and that that the women coming out “half a century later about a generally unpopular profession” could express “survivor bias”. ↑

-

This happened around the time of a lawsuit against Dezaki for defamation, supported by some of the historical-revisionist interviewees. Dezaki ultimately won the lawsuit (Rich 2019). ↑

-

In regards to the hateful actions of Makoto Sakurai and the Zaitokukai in front of these schools, the perpetrator states that “attacks on children are not acceptable” but that he agrees that “that an organization clearly supporting North Korea and whose staff are arrested as spies is dangerous, and that it should not exist in Japan.” Moreover, the act of wearing traditional Korean garments such as the hanbok and jeogori as a student is, to him, the equivalent of “being a child of active supporters of the world’s worst human rights oppression and dictatorship” and thus warrants being harassed, “just like if you dress up as a Nazi, you’ll get beaten up.” ↑

-

An message-board that served as inspiration for its English-language counterpart 4chan and retains the same notoriety within Japan. Since 2017 it has fallen under ownership of the operator of the far-right image-board 8chan, and was renamed to 5channel. ↑

-

Maruta – a loaded term due to its usage as a codeword for human beings experimented upon by Unit 731. ↑

-

The perpetrator admitted to not having read the manga himself, however. ↑

-

Tsuji defines the social category of ‘Netto Uyoku’ based on the following traits: 1) antagonism towards China and the Korean peninsula, 2) agreement with visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, 3) agreement with the revision of Article 9 if the constitution, 4) agreeing with the display of the national flag, and 5) stating political opinions on online blogs or social media (2008). Although an arguably dated definition that excludes historical revisionism, anti-communism, misogyny, distrust in established media, and an increasing shift towards libertarianism, his categorization is nevertheless strikingly applicable to the perpetrator’s views. ↑

-

An interesting similarity with Halle is that, due to strict gun laws in their respective countries, both the Halle perpetrator and Abe’s killer used self-manufactured guns built from easily obtainable components and based on manuals found online. In regards to gun-accessibility, on November 2019, the perpetrator tweeted: “If this were a free country, I would’ve shot myself in the head or gone on a shooting spree a long time ago. But I would have picked the right people to shoot.” ↑

-

Ostensibly focusing on ‘men’s rights activism’, the Manosphere is a loosely connected online community built around highly misogynist and anti-feminists views such as the ones portrayed above, and often intersects with far-right, neo-conservative subcommunities. ↑